Welcome to part two of a two-part series on the Evolution of F1 Sponsorship by aspiring Motorsport Lawyer, Anirban Aly Mandal. After evaluating stipulations regarding personal sponsors and racing overalls in part one, this article will focus on helmet designs and general sponsor expectations.

Helmet Design

Apart from race suits, driver helmets are pretty important real-estate for sponsors. Once in the cockpit, the crash helmets are the only visible advertising spots as far as the drivers are concerned. For the majority of F1 fans who watch the sessions broadcasted on live television, the crash helmets are pretty much the only distinguishing factor between drivers apart from the driver number and T-Cam colour – either of which aren’t part of the sponsorship package so to speak. According to Clause 3.9 of Senna’s agreement, he had the choice of having his name i.e., “SENNA” replace the helmet manufacturer’s logo on the helmet after such design and size were approved by both the team and the sponsors. On the flip side, Nelson Piquet had no say whatsoever with regards to the choice of placing any sponsors or his name on the helmet.

That being said, Piquet’s agreement stands testament to how meticulously sponsor exposure was regulated even back in the day. According to Clause 12 of his agreement, his helmet would have;

- Honda’s logo on the visor,

- the team’s secondary sponsor logo below the chin,

- a 35mm logo of the principal sponsor’s choice on each rear quarter; and

- a logo of the principal sponsor’s choice above the visor.

Once again, it is important to emphasize on the era-specific nature of these clauses. Back in 80s and 90s, crash helmets were beautiful yet simple designs – this also came down to the fact that the number of sponsors each team had been also limited. Those numbers have grown exponentially in the current generation of the sport. In 2023, the sport crossed an important milestone as it surpassed 300 corporate sponsors spread across the ten teams and F1 itself. Moreover, today, crash helmet designs are used by the drivers to express their creative and political outlooks. Naturally, modern driver agreements would envisage incorporating the following essential elements within the clauses to strike a balance between driver freedom and sponsor prioritising;

- The designs must not be offensive so as to negatively impact the brand association of the team and its endorsers,

- The designs must not be overly controversial,

- The designs must not infringe upon any third party’s intellectual property; and

- The designs must not undermine the team’s sponsors, in both design and intent.

Therefore, elements of Senna and Piquet’s agreement would have carried forward into a modern F1 driver’s agreement to strike the afore-stated balance. There are many examples on the 2024 grid that would give rise to this conclusion. Let us take the example of two of the most marketable teams in F1 i.e., McLaren and Red Bull to highlight how helmet designs are bound to be regulated.

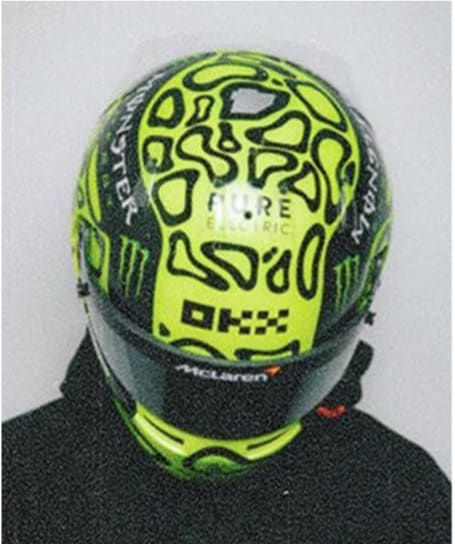

Pure Electric (Lando Norris’ father’s e-mobility company) and LN Kart (Norris’ karting venture) both feature on the British driver’s crash helmet. They are not partners of McLaren and are only Norris’ personal backers/ventures. The chin, visor and the space above the visor, however, are reserved for the team’s sponsors i.e., Android, McLaren and OKX, respectively. Similarly, Piastri sports Quad Lock (smart phone accessories company and Piastri’s personal sponsor) on his helmet, however, the team’s sponsors have yet again taken the most prominent placement and dimensions on his helmet.

Coming to Red Bull, Max Verstappen’s 2024 helmet places their title sponsor Oracle on the visor. It is noteworthy to say that while EA and Heineken (associated with both, Red Bull and Verstappen) are featured extensively on the chin and sides, Verstappen’s personal sponsor i.e., Viaplay, and Verstappen.com are allotted proportionally less prominent dimensions on the three-time world champion’s helmet. The same can be said about Sergio Perez’s personal sponsor, Kit Kat.

Needless to say, these details are not down to aesthetics. Rather, they are embedded meticulously in the respective driver agreements – much like in Senna and Piquet’s cases. It is to be noted however, that in Senna’s agreement all the allowances related to personal sponsors were qualified with the term ‘May’ whereas, obligations related to team sponsors were qualified with the term ‘Shall’. The inherent legislative connotations of the above clearly elucidate once again, that, in driver agreements, the preference is almost always given to the sponsors of the teams rather than to a balance of interests between them and the driver’s personal sponsors.

Sponsor Events & General Behavior

Once a Formula 1 driver associates himself with the brand of a sponsor or even the team, this association tends to become immortal. Hence, it becomes pertinent for modern driver agreements to (a) specify certain obligations with respect to sponsor duties that a driver must fulfil and (b) specify personal behavioural standards that a driver must maintain at least till the association lasts so as to not tarnish the image of the sponsors and the team. The ethos of the above could be seen even in the older Formula 1 driver’s agreements which can be extrapolated in the context of modern Formula 1.

In 1988, the Williams Grand Prix Engineering Limited team entered into a Sponsorship Agreement with the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation for the 1988 and 1989 Formula 1 season. The agreement went in-depth with regard to the obligations of the drivers towards the sponsor. According to it, the drivers were expected to:

- render their services to the sponsor to the best of their abilities and also ensure compliance to their ‘reasonable suggestions and recommendations’ in respect of such rendition, however, testing and racing would take priority,

- conduct themselves in such a manner so that it upheld the good name and goodwill of both, the sponsor and Williams; and

- to appear for any sponsor events that were held at the race track.

Interestingly, the agreement also contained a clause whereby the drivers were expected to drive in a manner that enhanced the reputation of the sponsor. It is reasonable to expect that the intent and content of the aforementioned clauses were inserted in the individual driver agreements that Williams executed for the 1988/89 season as well.

Moving on, according to Piquet’s agreement, he was expected to wear Team Lotus’ cap (containing the team’s sponsors) whenever he was at the racetrack and/or when it was appropriate, except for when he was on the podium, in which case he was obligated to wear a ‘Goodyear’ cap. Further, he was obligated to provide a total of 20 days per year to the sponsors for personal and promotional appearances. Senna’s agreement has on more than one occasion highlighted the extent of Senna’s responsibility towards the sponsors, however, its essence was condensed in a clause that stipulated the following:

- Senna must conduct himself in a manner that upholds the name of the team and himself while dealing with the media and the racing fraternity,

- Senna must cooperate fully with the team and sponsors with respect to promotional and social functions; and

- Senna must ardently comply with the test programme.

If we were to summarize the very essence of the aforesaid clauses, it would amount to the following: Driver presence and good conduct so as to enhance the brand association of the sponsors and the promotion of their products. The importance of brand association and marketing has not reduced since the 80s and the 90s, if anything, it has only multiplied. Hence, in the context of a modern Formula 1 driver’s agreement, clauses related to sponsor events and general conduct of the drivers whilst representing the team and the sponsors would aim to achieve the following;

(a) Procurement of the presence and involvement of the driver in sponsor and promotional events,

(b) Fulfilment of media duties by the driver whereby his association with the sponsor can elevate the image of the sponsor,

(c) Ensuring good, responsible and reasonable behavior and conduct of the driver whilst the driver is representing the team and the sponsor; and (d) Maintaining an uninterrupted and reasonably constant association between the sponsor, its products and the driver during the subsistence of the contractual relationship.

Conclusion

F1 driver agreements are a multi-faceted edict of rights, options and obligations. Given the nature of the sport, the nature of these rights and obligations varies drastically and can represent performance, remuneration, indemnity etc. But the business of racing also demands a proper glance whilst preparing these agreements. The preceding discussion aims to highlight the various factors involved in developing frameworks for motorsport sponsorship within the sport.